I had a long discussion with a radio producer on what I thought was wrong with the Autumn Statement. We discussed the numbers but what I said is most important is not what was said, but what was not. That’s where the frightening bits are.

It was a very long time ago that I realised that when looking at financial data – whether accounts or economics information – the key thing to look for is what is not made available.

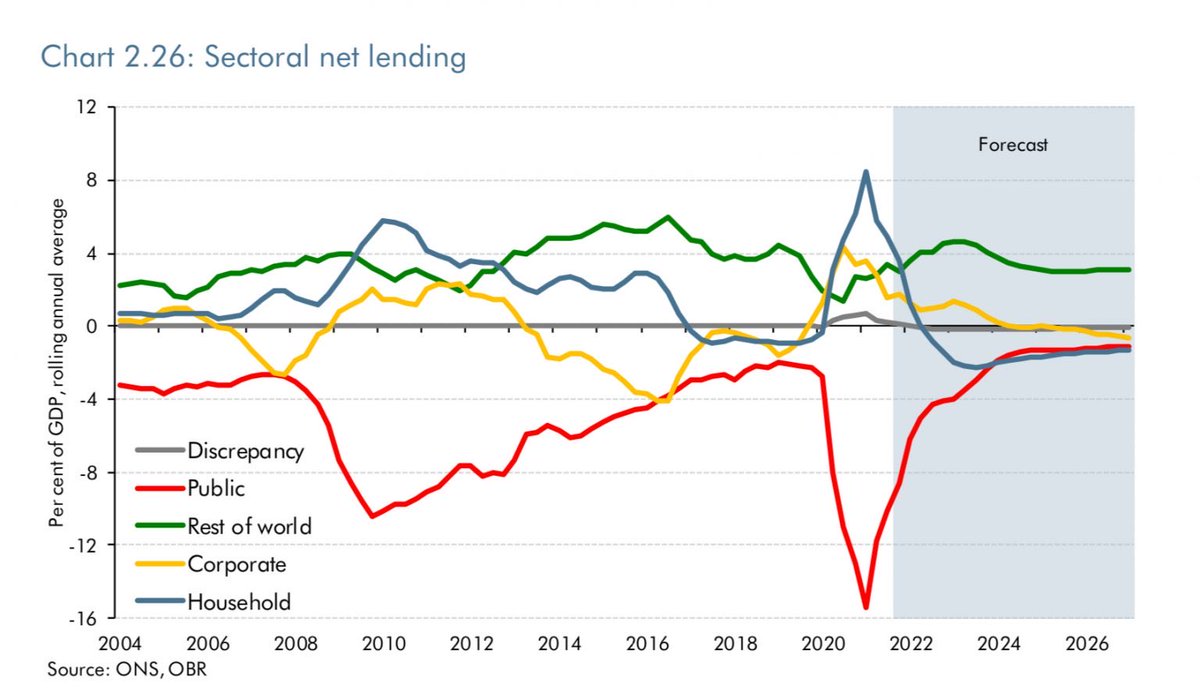

There was one critical chart missing from the Office for Budget Responsibility report, which was of the sectoral balances. This charts shows which parts of the economy are borrowing and which are saving. This was from March 2022:

You will note there are four sectors that cover all activity in the economy. They are households, business, the government and overseas holders of sterling. All sterling transactions fall into one of those groups.

Double entry requires that the sectoral balances add up to zero. For every borrower there must be a lender, as a matter of fact. The earlier chart shows this. So, the question is, why hasn’t this been published and what might happen?

First, we know that the government is going to borrow. The forecast is for £170bn plus this year, and well over £400bn in all over this period. But we also know from the forecast that the OBR envisage no apparent net savings by the private sector over the next five years.

It’s harder to predict what business will do, but I see it saving: that’s the result of limited investment in a recession.

What we really do not know is what is forecast for the overseas sector. It’s unacceptable that this is not forecast.

But let me explain what really worries me. As we know, Hunt has focused all his attention on government debt and pacifying the financial markets. The whole focus was on meeting a fiscal rule he made up for the Autumn Statement solely so that he could say he met it.

The result of this has been obvious. As we know, households could (and the estimates vary) lose up to £4,000 a year – but this is an average, of course. We know some households – the top 10 per cent – will still do just fine, and will be saving. It’s the rest that worry me.

If the top 10 per cent of the wealth profile will be saving – and I have no doubt they will be – then over the next five years the rest of the UK is going to be borrowing very heavily in proportion to income. And for some this is going to be unsustainable.

Five years of mortgage rates at 5 per cent or more is going to bring unimaginable financial stress. And since mortgage rates roll straight over into private rents those in that sector are also going to face intolerable stresses.

But that’s not the end of the matter. Almost certainly, inflation is going to fade away by early 2024. But what we know is that we have a government determined that wage settlements will not match the inflation that will have happened by then.

That means millions of households will not only have more cost – in real terms they will have less pay. It’s OK to protect pensioners, those on benefits and minimum wage, but those from about the 30 per cent mark in the income range to maybe 70 per cent plus are getting no protection at all.

But it’s worse than that: they are being sacrificed to the goal of the government meeting a meaningless fiscal rule. No wonder the sectoral balances were not published.

My fear is that these households will face financial burdens they simply will not be able to pay. Whatever the additional cost is – and for this group it is going to be well above the average – it’s not possible to say ‘just tighten your belt’.

The reason for that is quite straightforward. The need to pay the mortgage, council tax, fuel bills, water and put food on the table will not go away. It’s fixed, and it is much more expensive. And there will be less money. Lower real pay and higher taxes guarantee that.

No doubt the Treasury has assumed that this group will dip into their savings. The slight problem is most of them don’t have any of any significance. Or the Treasury assume they will borrow. And it is true that, for a while, some will; for example, mortgages will be extended.

But, and I stress the point, this ignores the real issue. Over time, more and more in this group will run out of lines of credit. The straightforward impossibility of their situation will become more apparent. And the hardship being imposed will become very clear.

I am quite sure that some in the 10 per cent will be contemptuous of that hardship. I already hear comments like ‘they should not have assumed cheap credit would last forever’. Or ‘don’t they know we’re in a recession: of course it will be tough’.

But the truth is that people in this group – those on average incomes – took cheap credit to buy houses at inflated prices because it was the only secure housing option available to them. And yes, they did and do expect some extras in life for them or their children.

No one in this group is at fault for thinking they should be able to afford their costs of living. And my fear is very large numbers of them will not be able to do so. And not just be a bit, but by quite a lot.

In real terms they may be missing over 10 per cent of their household incomes and most households will simply not have that margin for error available to them. Many will also not be able to borrow that sum – because they could not repay it.

In other words, what the Treasury and the Office for Budget Responsibility failed to mention was that in their desperate desire to make it look like the government was managing its debt, they have planned to pile totally unaffordable debt onto million of households.

There is, as I have long argued, a difference between governments having debt and households being in debt. Households have to repay their debt using money they earn. Governments don’t have to repay their debts (and rarely have) and do so when it happens using money they create.

In other words, governments can always manage and afford their debts and households cannot. The difference is as simple and stark as that. But what the government has chosen is to pile the debt on those who cannot afford the debt when government itself could easily have afforded to accept it.

Of course, I could at this point just say this was a mistake. But it is much more than that. For the households involved this is a disaster. But again, that understates things. Because for the whole country this is a disaster.

There are always some households who cannot afford to pay their debt, and the financial system can survive that happening. But when millions cannot pay their rent, mortgages and bills, and when people cannot feed their children, the system cannot survive. It will break down.

What this Autumn Statement has set up is the biggest potential economic disaster since way before living memory where household debt default will be commonplace and those owed the money – from banks, to landlords, to energy companies and more, will not be able to handle that.

In other words, this will not just be a financial problem for the households involved in this disastrous situation: we face banking and corporate meltdowns too.

And that is all because the government refuses to believe that it can and must take on the job of creating the new debt – or money supply – that the country needs to survive this crisis.

And I stress, it is money supply that is needed to get through what is going to happen. Inflation creates a shortage of money. If money is worth less we need more of it to keep the economy going. It really should not be rocket science to work that out.

There are only two ways to make more money supply. Either the government creates the money by spending more into the economy than it taxes and borrows back from that economy, or the private sector banks have to create it by lending more to people who want to borrow.

There will be plenty of people wanting to borrow. There will be few banks wanting to lend, however, precisely because it will be obvious very soon that those wanting to borrow will not be able to afford to repay. So, that private sector solution is going to fail.

Alternatively, the government should be creating the new money that we need right now. That is, after all, its job as the creator of the state’s currency. But what Hunt has said is that it is going to duck that responsibility.

Even worse, the Bank of England is going to try to sell the bonds it already owns as a result of QE to try to reduce the money supply still further over the coming years, all with the goal of keeping interest rates ruinously high.

That means the government is not just ducking its responsibility to create money, it is actively planning to make things worse via the Bank of England.

And what that means is that nothing about the Autumn Statement adds up. The numbers we have heard so far are bad. But what is really troubling is their implication, for household, then corporate, and then whole economy failure, and all because the government will not create money

This Autumn Statement is not inevitable, as Tories and Labour alike seem to be saying. The austerity it imposes is not required, as they suggest. The pay clampdowns they both seem to desire are deeply undesirable. And high interest rates are recklessly irresponsible.

We do not need to have an economic disaster in this country in the years to come. But as things stand we will. And it will have been manufactured here, firstly by the government and right now by Labour failing to spot what the government is doing wrong.

This can be avoided. Tax cuts, spending increases, more government borrowing and probably QE, and lower interest rates are all required. And there will be no inflation of consequence. And with the right explanation to the City, the package can be sold to them.

But that will take a very confident Chancellor sure of the power of the state to make lives better. Have we got one of them? I can’t see one being available right now. But whatever happens we are going to need one soon.

That’s because as night follows day we are heading for a disaster. We can avoid it. But only be accepting that it is the state that has to get us out of the situation we are in, and that piling more debt on households can only make things very, very much worse.

The Treasury and Office for Budget Responsibility have not told us the whole story on debt in the hope that they might get away with it. They won’t. And the result will be very costly for us all.

You can read more from Richard on his blog: Tax Research.