No apologies for reproducing yet another Twitter thread. Everyone should have the chance to read this. Ed

The 1970s was a decade of serious anxiety about food supplies. Norman Tebbit, of all people, urged the government to consider rationing basic foodstuffs. That played a significant role in the decision to join the EEC, and raises some important questions today. [THREAD]

The UK has not been able to feed itself since the early C19th. Even for an industrial economy, it is unusually dependent on imported food. And by the 1970s, a mixture of bad harvests, population growth, inflation & the collapse of Commonwealth agreements was starting to bite.

In 1974, for example, Caribbean sugar imports dropped by a third, as producers abandoned Commonwealth trade agreements and sold to more lucrative markets elsewhere. Supermarkets introduced informal rationing, and consumer organisations urged the public to stop buying sugar.

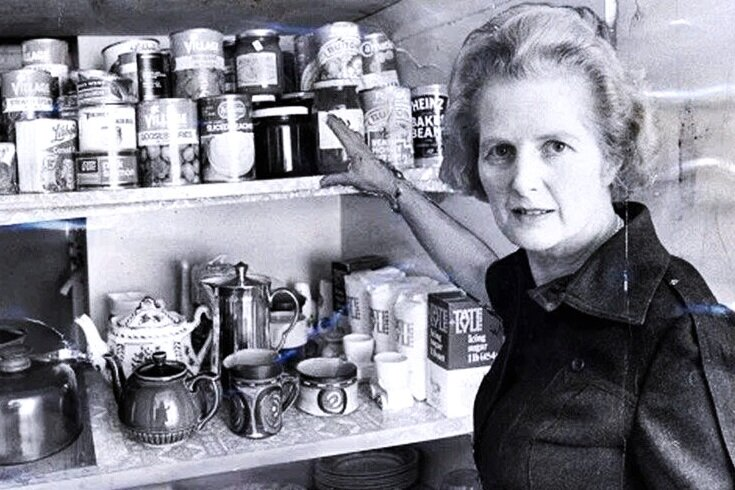

Later that year, the Ministry of Agriculture warned that Canada might suspend grain exports if the currency continued to decline. In November, Margaret Thatcher had to open her cupboards to journalists to prove that she wasn’t hoarding food.

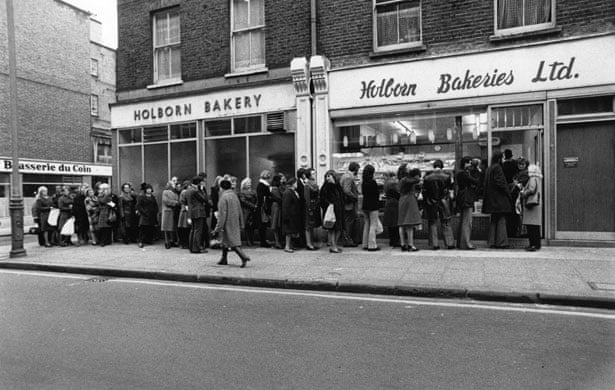

1974 also saw a bakers’ strike, in response to rising costs and falling real wages. Some suppliers restricted shoppers to a single loaf each, prompting queues outside bakeries at dawn. Conservative MPs again raised the prospect of rationing.

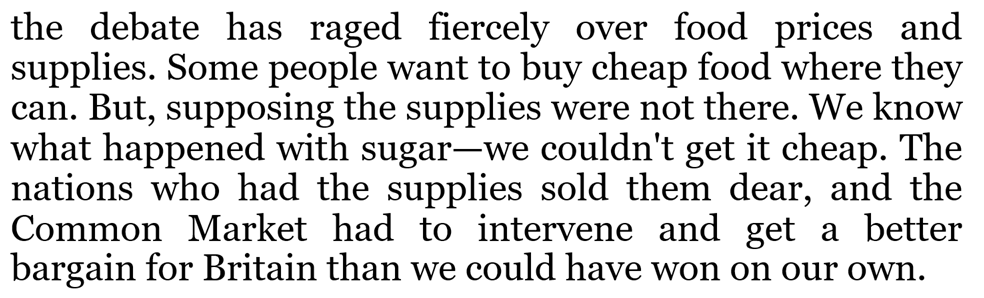

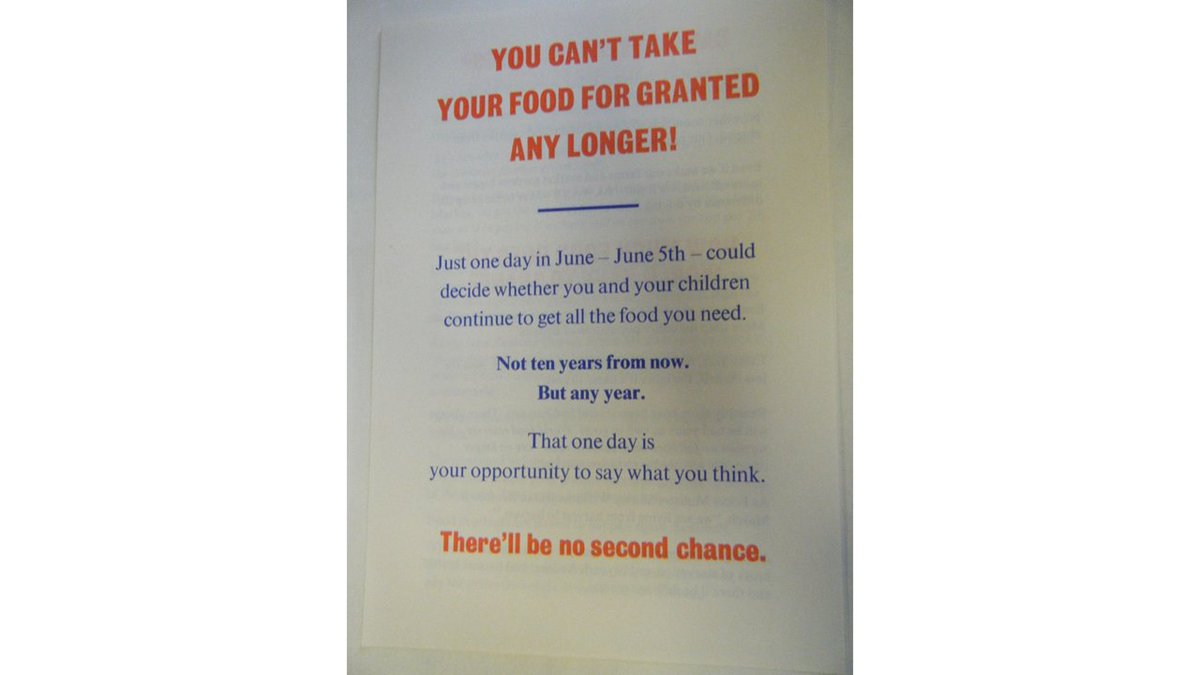

The UK had joined the EEC in 1973, but was still operating under transitional arrangements on food and farming. So the 1975 EEC referendum saw a serious debate, of the kind we don’t seem to be capable of anymore, about what leaving might mean for the supply and price of food.

Leave campaigners argued that prices would be higher in Europe, because production costs were greater and the Common Agricultural Policy was designed to ensure farmers a decent wage. Barbara Castle compared shopping bags in London and Brussels, as a warning against EEC prices.

Pro-Europeans responded by pointing to rising prices across the world. The days of cheap food from compliant colonial markets, they warned, were over. European prices might, in some years, be higher, but Britain would at least have a guaranteed source of supply.

As Margaret Thatcher warned: “In Britain we have to import every second meal. Sometimes we shall pay less in the Community, & sometimes we shall pay more. But we shall have a stable source of supply, & most housewives would rather pay a little more than risk a bare cupboard”.

The leader of the National Farmers’ Union warned of “a clear threat to continued regular food supplies if Britain left the Market”. Voters were urged to think of the EEC as “the Common Super-Market. Well-stocked shelves; plenty of choice and just around the corner”.

The food economy has changed radically since the 1970s. Production has boomed, transportation has improved & prices have fallen. At the same time, Britons have become less suspicious of “Continental” food, & used to abundant supplies reliant on “just-in-time” delivery chains.

Yet food poverty remains a desperate social problem. In the year *before* the pandemic, foodbanks gave out 1.9 million food parcels. The poorest 10% of households spend more than double the share of income on food of the richest. If prices rise, we know who will suffer most.

47 years after joining the EEC, it’s legitimate to ask whether the old arguments for membership still hold. What’s less forgivable is the stunning incuriosity of those tasked with delivering Brexit about why Britain joined, what changed with membership, & what’s now at stake.

Perhaps Brexiters can find better solutions to the challenges that drove the UK to join. But pretending those challenges did not exist – as if Conservatives like Thatcher, Heath & Macmillan embraced membership in some bizarre spasm of irrationality – is a recipe for disaster.

Brexit requires us to rethink nearly every major policy choice since 1973. If we don’t understand why those choices were made, we won’t be ready for the decisions that lie ahead. If tweeting for lolz is the best we can do, the joke will deservedly be on us in 2021.

Originally tweeted by Robert Saunders (@redhistorian) on 11/12/2020.

Robert Saunders specialises in modern British history, from the early 19th century to the present, focusing particularly on political history and the history of ideas. He taught at Oxford University from 2004 to 2013, and has held two visiting fellowships at the Huntington Library in California. When time allows, he blogs and has a personal website .