A sticker with Ukraine appeared on my car just after Russia began its new wave of invasion into Ukraine. I know, it’s just an empty gesture, but I simply wanted to express somehow my solidarity with the victims of Russian imperialism. For the 6 months of 2022, while I still lived in Scotland, this sticker was met exclusively with positive reactions, people were asking me where I bought it or if I have some spares. I drove my car across all of Europe and encountered a few similar reactions. But after I arrived in Finland, I noticed some change. True, some people took me for a Ukrainian refugee and even offered their help, but it turns out that such a decal on one’s car is too much to bear for some.

The fact that for the first three months – until I managed to register the car in Finland (thank you, Brexit – you definitely did not make it easy!) I also had a UK sticker on it. As many people never heard about Boris Johnson dropping the time-tested GB marking for a British car, many people assumed it means Ukraine.

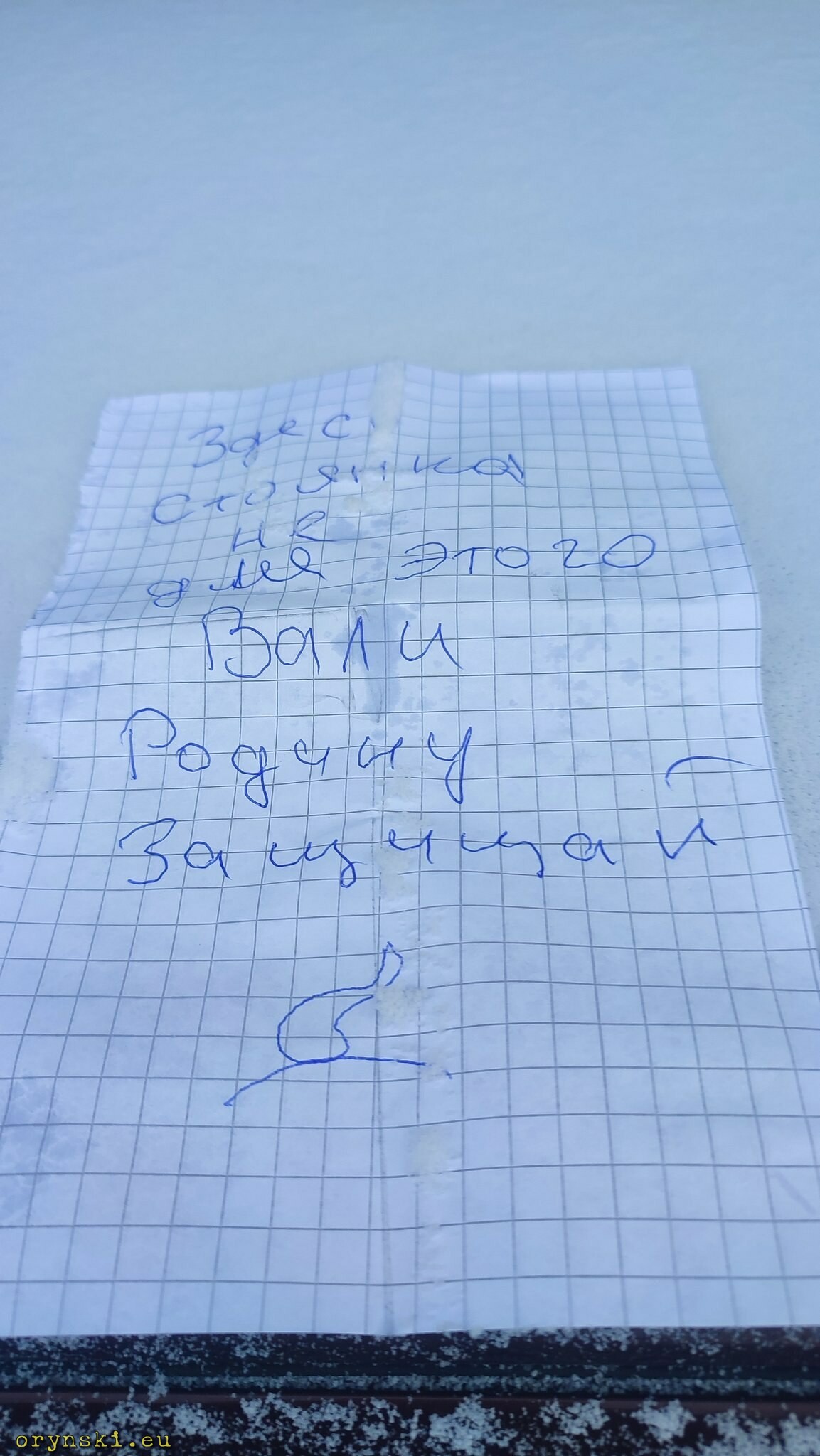

And so one day I came to my car to find this “nice” letter behind my windscreen wiper. Its author lectures me, as I am told (I can’t read Russian) that this is not a place for me to be and I should get back to Ukraine to defend my “shithole country”.

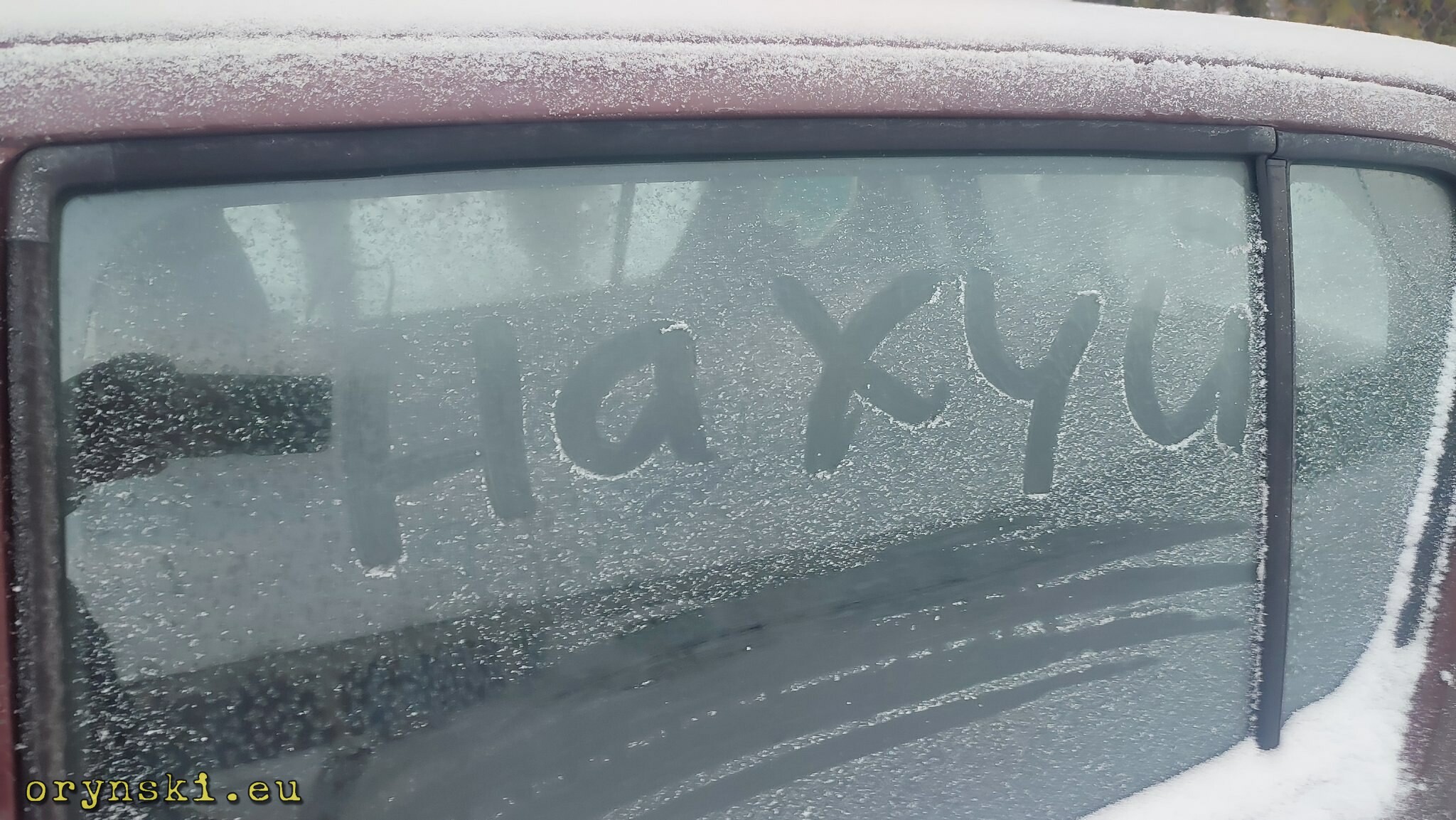

On my frozen window, someone also wrote with their finger a piece of useful route-finding advice, telling me to follow the path of the black sea flagship cruiser Moskva, apparently.

During this festival of friendship, someone also spat on my windscreen (the saliva had frozen and I had a hard time scrubbing it off) and tried to break off my wing mirrors (luckily for me it’s not so easy, as they fold both ways so no damage was done). Someone also tried to scratch the Crimea bit of my Ukrainian-shaped sticker, but they failed in that task (oh, the irony).

That was a month ago. I reported it to the police, but they dropped the case due to the impossibility to find the perpetrator. Today, when I arrived at my car, I noticed that someone tried to peel off my Ukrainian sticker again. There were footprints on the snow, suggesting someone approached my tailgate, and the sticker was peeled out for the most part. Around here it started to tear, so the perpetrator left it as it was.

I never experienced such problems in Scotland. And it’s already the second incident in the short time I live in Finland. Why would that be? Could it be that Finns are more hostile towards Ukraine and fluent in Russian?

I have another theory. The main difference is that there were barely any Russians in Glasgow. And there are plenty of them in Helsinki.

I know I just described to you two relatively insignificant incidents. But the situation with the Ukrainians harassed by Russians in public spaces in Western Europe is, unfortunately quite common. I guess I became a target as well because some vatniks assumed that I have to be Ukrainian, too. And in my opinion, this shows that Russians should not be let in so easily into civilized countries.

I know, I know, you might say they are innocent, they weren’t supporting Putin, that they are also victims of this whole situation and that even during the time of the Cold War Russian dissidents were welcomed as refugees in the West. This might be true, but there is a significant difference: if you decided to escape from the Eastern Bloc, it was a one-way journey. You had to leave everything behind and the bridge burned down as soon as you crossed to the other side. Today, Russians just want to enjoy their comfortable lives. They won’t go out to protest, because this is too dangerous for them. And the question of how many of them would protest if it was safe to do is still unanswered. We have to stop pretending otherwise: the fact is that many Russians do despise Ukrainians and actively support Putin’s actions; at least, until they are drafted themselves – many aren’t patriotic enough to risk their own lives on the front line. They run away to Georgia or to the West because they are against it. Not against the war. Against having to fight it.

This is a typical “eat a cookie and have it” scenario. While in Russia, keep your head down and pretend to not be bothered by Vladimir Vladimirovitch’s actions, even if in private you condemn it. And then go to the West and play poor victims of Putin’s regime. At least when people are looking. Because when you feel safe enough, you can always write some anti-Ukrainian slur on Facebook, spit at a Ukrainian refugee, or try to damage a car marked with letters similar to the beginning of the country you hate so much.

Even some of my Russian friends, whom I always admired, disappointed me. I do understand – if you live in Russia, you first have to think about your safety. Not everyone has to be a hero. I would not condemn anyone for keeping their heads down. But I would expect at least some basic human decency: if your choice is to sit quietly when thousands of innocent Ukrainian civilians are being murdered by the army of your nation, at least keep your mouth shut when desperate Ukrainian share their frustration online. Really, the fact that someone wrote a few swear words on the Russian model’s Instagram page is not exactly the greatest human tragedy nowadays. You don’t have to rant about Russophobia, especially if you claim you are not falling for the Russian propaganda. Because if you can’t understand that those angry voices aimed at a Russian celebrity who on social media shows she can live as if nothing happened are just a result of the desperation and anger of the citizens from the nation your nation decided to lead a campaign of total destruction against, then I have a feeling that that propaganda, pumped into society via Russian TV that you claim to not be watching, somehow made its way into your mind, too.

And let’s remember that this is not some babushka who spent all her life in some village lost in the endless forest of Siberia, who only hears about world events on TV (provided the electricity is on). This is a young person, formerly living in Poland for more than a decade, who knows languages, has access to western media, knows how to use VPN and so on. I am sure that the majority of the younger generation knows exactly what is going on. They just pretend this does not concern them. Like in that joke about those two Russian guys locked in a moving cattle car. “Do you know to which Gulag they are sending us?” asks one of them. “Don’t care, I am not into politics” – answers the other…

There were many discussions about why Russians are passive and why they are not protesting. Much wiser people analysed this. The question we still don’t know the exact answer to is how many of them don’t protest because they are afraid, and how many of them don’t because they actively support the war, or at least don’t want to lose their comfortable lifestyle. Not so long ago, when I tried to ask my Russian friend about what real Russians think about it and how one can live in a country that is conducting such inhumane actions, I was met with very skilful subject change and heard a lot about how comfortable life in Moscow is and how great the living standards is there, even despite the sanctions… But even if your passivity is caused by fear, is that a good enough excuse to evade the consequences of Putin’s decision?

Of course, blanket responsibility is not good. In the perfect world, where everyone has complete control over their lives and, as we joked when I studied physics, every person is just a perfect sphere travelling in a vacuum without friction, this would be good enough. But the world is more complicated. If you are a citizen of some country, even though in most cases it was not by choice, you are a citizen for good and for bad. It can have some perks, but often there are also consequences of the political decision of your leaders. For example, Britons now have to queue at the borders to have their passports stamped while EU citizens are just flowing past them smoothly. Nobody says “let’s let those Britons pass, too, surely they weren’t voting for Brexit?” No, since Theresa May said Brexit means Brexit and pulled the trigger and Boris Johnson got Brexit done, they have to live with the consequences of those political decisions. And are stuck in those queues and can’t demand special treatment. This is what being a citizen of a country means. At least they can be happy they don’t hold a Somali passport, as in that case crossing the border would be even harder for them.

So why it should be different with Russians? Why, when Ukrainian cities like Mariupol or Dnipro are being razed to the ground by Russian artillery, can’t we be at least annoyed by the hypocrisy of Russians, who on one side don’t want to put their comfy life in Moscow or St Petersburg in jeopardy, but at the same time still demand rights to enjoy their holiday trips to Tuscany or shopping in Helsinki’s Ikea? Why should we all assume they are victims of Putin’s regime?

There is no doubt: Russia has to be stopped from spreading. Putin is cancer that chews its body. I used this comparison before and I believe it’s still valid: we tried to treat this cancer with pharmaceuticals: international cooperation programs, common business enterprises, and so on. It was not fruitful. Then we tried some precision surgery: carefully tailored sanctions, and bans on certain individuals from Putin’s regime. That also brought no effect. The cancer is so bad, that the only thing left is chemo. During chemotherapy innocent cells will suffer – this is how it works. But sometimes there is no other option. Russia is already at this stage. True, it might be tough to be an ordinary Russian today, but I doubt anyone of them would like to swap their lives with someone from Mariupol or Bakhmut. And the world needs to decide what is the most important thing. If the fire engine arrives at the scene and pushes away some cars to be able to reach the family in the burning flat with its ladder, nobody is crying about the poor guy that would need to repaint his bumper.

Anyway, those moral deliberations are valid only when we think about those poor Russians that just want to put their heads in the sand and go on living as before, pretending that the war has nothing to do with their lives. But it’s much worse. Just browse social media, even western ones if you can’t read Russian. You will see many real Russians (because Kremlin bots are a different story) that openly support Putin’s regime while enjoying their life in the West, sometimes for decades. How many new ones like that do we let into the EU every day? How many of newcomers might not have enough patriotism in their blood to go to Donbas with 40 years old Kalashnikov, but still enough to actively support their country’s politics while enjoying safety in Helsinki or Warsaw?

There is also that thing that even Russian media admits: that Russian draftees lack equipment. Their communities crowdsource money to buy them military gear. If we consider Russia’s illegal invasion on Ukraine a terrorist act, surely this has to be viewed as open support of terrorist activities? Would we let to the EU someone, of whom we know he was crowdsourcing money to buy military gear for the soldiers of the Islamic State? We regularly refused entry to people who support Islamist organizations, calling them hate preachers and arguing they are dangerous. Even ordinary citizens from countries considered by our government to be risky are only let in after very detailed checking, and some of them are taken under the surveillance of counter-intelligence operations and deported when they step over the line. Why don’t we see Russia as one of such dangerous countries and all its citizens as a potential risk to our safety?

There is a lot of talking about providing Ukraine with more military support so it can push invaders away from its territory. And rightly so. We should provide as much as we can as soon as possible. But we are late for at least several months to the discussion of seriously redrawing our visa regimes for Russian citizens.