Rishi Sunak has a choice to make in his upcoming budget. He could provide the support most households in the UK will need if they are to be able to pay their bills in the next year. If he doesn’t provide it, we are in meltdown. This is Richard Murphy’s article on the impact of price changes we were expecting as a result of government policy, Brexit and Covid before the war with Ukraine, plus those we’re now getting because of it. Stick with it. Everyone’s going to be hit hard by what the government is letting happen….

In case this article is too long for you, this is a summary. We’re in a crisis. Energy and food costs are going to increase the cost of living of low-income families by 14% a year, or £300 a month. More than 70% of households will go into debt unless they cut their spending, a lot.

Given that most households will not be able to borrow to cover costs there is a massive economic recession coming our way instead as families cut out discretionary spending. The leisure sector will be hammered. Unemployment will rise. Banks will suffer massive bad debts.

Sunak should know this. If I can predict it based on data in this thread so can the Treasury. He needs to take action. He can afford to – tax revenues are way above budget – and by using QE if need be. Doing so he could peg energy costs and beat inflation.

Will he? That’s the question I am asking as I lay out the evidence and what he could do in this thread. If he doesn’t, you need to worry, because within a year we could be in meltdown. The evidence is in what follows. It may be the most important thread I have written.

I recently highlighted who might gain from the potential increase in average UK domestic energy tariffs from approximately £1,200 a year, to about £3,000 a year, as current fixed cost energy supply contracts now imply to be likely.

As I noted, most of the benefit of this increase in profits will go to energy companies located somewhere in the supply chain between the point where oil and gas comes out of the ground and where that energy does through a wall into your house.

The increase in profit to your actual energy supplier will be fairly small. In fact, the government benefits a lot more by collecting more VAT and by dumping the cost of failed energy companies onto you through increased daily standing charges.

That does, however, mean that most of this price increase benefits other companies in the supply chain. My estimate is that their share of your annual payment might increase from £43 a year to more than £1,700 a year, a near enough 40-fold increase.

As I noted when I first wrote about this, the only appropriate description for this is exploitation. You are being ripped off simply because governments are collectively letting the oil and gas companies and oil traders get away with this.

The object of this blog post is to consider what the implications for some sample UK households of these energy price increases, and some of the other changes in both income and prices, might be. After all, it’s not just energy that is changing in price.

It is my belief that until we do understand what these impacts on real people might be that it is unlikely that we can properly appraise the appropriate responses to be demanded from energy companies, the government, and others to tackle the poverty crisis that we face now.

For the purposes of this exercise, I am using data supplied by the Office for National Statistics on household income and expenditure. This is available here.

As usual for the ONS, this data is a little out of date. It relates to March 2020. It’s also a bit ‘clunky’. By that a mean it’s presented in a fairly cumbersome style and to use it I have had to do some summarising and rounding.

That rounding means that some of the data in the tables I present in this thread does not quite add up. Don’t yell at me! I used what I had to work on and have done my best to turn it into something that makes sense. What I ended up with is plenty good enough to be useful.

Importantly, this data is split into what are called decile groups. For those not familiar with deciles, they split data on a population into ten groups of equal size, in this case including an equal number of households in each group, with each group having a broadly similar income.

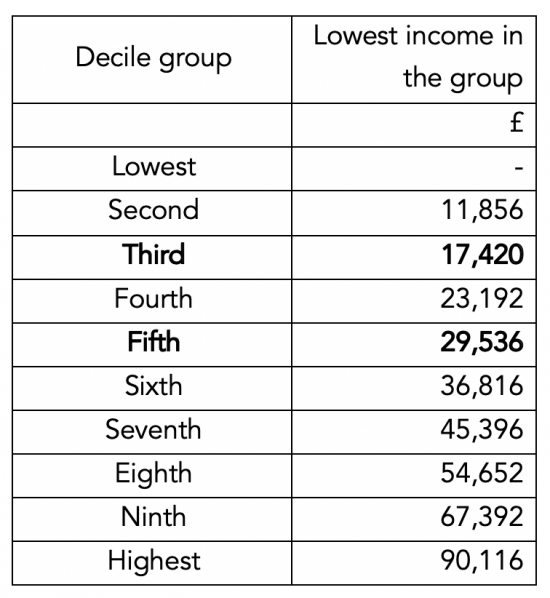

Using the ONS data, the deciles of equal size split by income group in March 2020 were split as follows into income bands, with income being stated before tax:

My work concentrates on those who are in the third and fifth and top bands. Those in the third band have income of about £19,100 a year on average after tax. On average people in this group earn just a bit more than the minimum wage, working full time.

I also chose to look at the fifth band, where average income after tax is about £29,500, or very close to UK median earnings at present. Before tax, and assuming a single income earner in the family, earnings would be 33,400 per annum.

It is important to note that I am assuming there is only one income earner in the household when making these observations. There may, of course, be two.

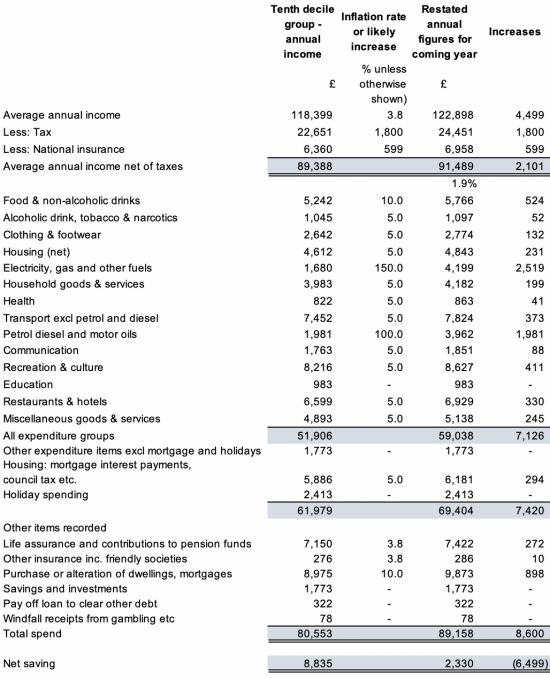

To provide contrast to these two groups I also looked at the tenth decile – the top income earners. They have average pre-tax income of £118,400 a year. After tax they enjoy £89,400 at present according to the ONS. Obviously, some at the very top enjoy very much more.

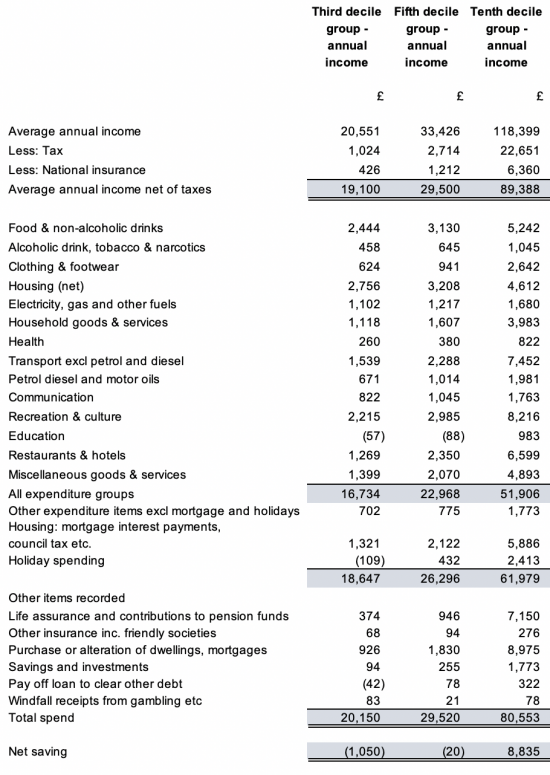

Having summarised the income, tax and national insurance paid according to ONS data for these groups I then also summarised their average spending according to the ONS. I had to do this under broad headings. The actual data is many pages long and more detailed than shown here.

If I just use the data for these three groups as the ONS presents it then it is as follows:

There are three things to note straightaway. The first is that the ONS data implies that the third decile – the minimum wage earners (near enough) don’t already make ends meet. It’s not clear how the ONS explain that, especially as their savings are already small.

The fifth decile – the average earners – broke even in March 2020, near enough. And the top decile of income earners were doing just fine, which is no real surprise to anyone because that’s the way our society is stacked.

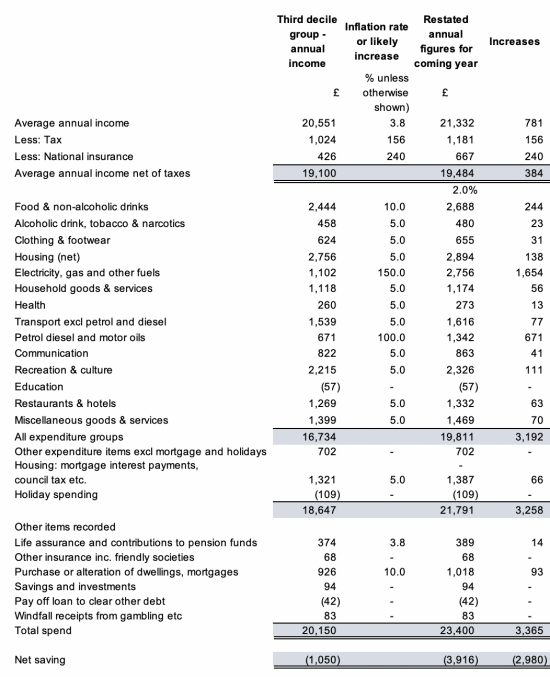

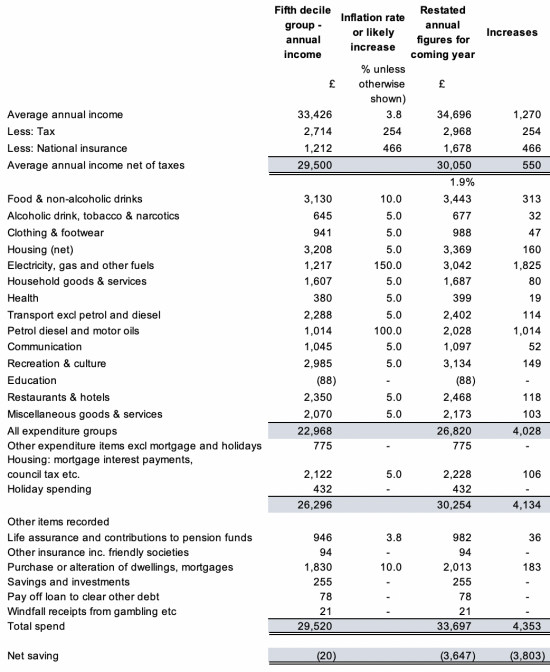

Having established this data I then had to make some assumptions on relevant inflation rates to suggest what might happen. On income, I have assumed 3.8% pay rises – because that is the latest ONS estimate of pay rises, excluding bonuses.

Tax increases are based on the estimated pay rise at the appropriate tax rate assuming no increase in personal allowances, which is what is happening – so taxes are increasing in reality, as I show.

For national insurance I have allowed for the NI due on the increased income and the increase in rate of 1.25% overall income. Because NI is capped for high earners the calculation is different for the top decile than it is for the two lower deciles.

Thereafter I have assumed 5% inflation on most spending – which is consistent with most current forecasts (although if I am honest, I think these may be a bit low now), but there are obvious exceptions.

On food I have allowed 10% for the lower deciles and 5% for the top decile – because they have more flexibility and the ability to substitute products. The 10% is based on Jack Monroe’s work and may be an underestimate. It may be worse as wheat shortages hit.

Domestic energy I have estimated at 150% as that seems to reproduce the prices we expect. Petrol I have estimated at 100% – or a doubling in the cost, which latest expert forecasts suggest likely.

I have assumed no increases in some discretionary costs. Most housing costs are hard to estimate because they vary so much. I have allowed for interest rate rises (very approximately) on mortgage costs. There is a lot of give and take here depending on people’s circumstances.

Putting all this together the impact on people in the third decile of income earners (those on about minimum wage, working full time) is:

The impact on those on approximately median income is:

And the impact on high-income earners is:

What this means is that those on about minimum wage have a cost-of-living increase of about 14%. Those on median pay have an increase of less, but still of an eye-watering 11% a year. And those on the highest incomes see a much smaller increase of about 5.3% in the way I estimate it.

Remember all these numbers are approximate, and they are forecasts, but I offer them in good faith. If the government does nothing to help people in Rishi Sunak’s statement next week, then I suspect that outcomes like this (or maybe worse) might happen.

Let’s put hard numbers on these forecasts. Those in my lowest income group will spend £65 a week, or £3,365 a year more. Given they had no money to spare before this began they are now in a desperate situation. After pay rises they’re still down about £3,000 a year

I don’t say that lightly: I am incredibly worried about those on lower incomes right now. Brexit, Covid and government policy – all of which were pushing up inflation well before war began – are pushing millions of households in this country into near impossible poverty.

I stress – these families are facing near impossible situations. Let’s not beat about the bush. Without much more help I can’t see how their household budgets can come close to adapting to the additional costs that they face. There is no slack to cut.

Life is not going to be a lot better for those on average or median pay. They will see their weekly costs rise by £84, which is an additional annual spend of £4,350. They were breaking even before this. Now they aren’t. They’re going to be down £3,800 a year after pay rises.

Just like those earning £10,000 or more less than them, many in this group will not be able to make anything like the demanded level of lifestyle adjustments that this level of additional cost will require.

What is also apparent is that if they do try to make that adjustment – and most will be forced to – then the savings will come from their recreation budgets – for which there is going to be little money left in both groups if anything like the required savings are to be found.

The top earners actually suffer bigger increases in actual costs as a result of the inflation that we are going to see. On average they face additional spending of £8,600 a year. This is despite having earnings increases of £4,500 a year. Two cars and bigger houses have a cost.

The best off will differ from the other groups in one way: they will still be able to cover their outgoings including all their planned savings, pensions and mortgage payments. Their options on how to address the issues arising are much wider than those available to others.

There are some interesting comparisons to make before considering the consequences of all this. For example, the same 3.8% income increase is assumed for everyone, but for the lowest earners that results in a 2.0% net pay increase; the median earners get 1.9% and the top 1.9%.

Those lowest off pay slightly less in national insurance increase overall than the median earners in this group, and the top group have higher income tax increases to compensate for smaller NI increases. But there is nothing remotely progressive about this.

Importantly, overall tax rate on inflation driven pay rises next year might be as high as 50% overall, given the impact of national insurance changes across the board. There is in that case no pay solution that is going to solve this issue, although cutting the NI increase would help.

What is more, net pay rises are only 11% of cost increases for those on approximately minimum wage, 12.6% for those on median pay and 24.4% for those in the top decile. No one is getting a pay rise that compensates for their extra cost of living, but the rich are doing best.

In that case there are three questions to ask. First, does this matter? Yes, because as it stands it’s likely that well over half of all UK households are going to face financial pressure they simply cannot manage over the next year as things stand. That is a nightmare for them.

It is also a nightmare for the government. These people will get very angry when faced with an insurmountable burden requiring that they cut back on everything but the most basic things in life, and even then will be challenged to make ends meet.

Politically we have not seen anything like this in the lifetime of anyone now living in the UK. How people react is anyone’s guess. But I know that a mother who cannot feed her children is one of the angriest people on earth and there are going to be millions of them sometime soon.

To be blunt, I am not sure how this situation can exist without the risk of serious civil unrest, which it would be very easy for people to have sympathy with.

Second, my analysis only concerns the initial reaction to price rises, as people try to pay. As struggling households cut all their leisure spending back, or end it, the secondary reaction is going to kick in. That means large scale business closures, and then mass unemployment.

You cannot force most people in the country to spend all their income on basic costs of living and maintain a thriving economy. That’s impossible. And £150 here or there on a saved council tax bill, or a bit saved on deferred payment arrangements is not going to solve that.

The leisure, tourism and travel sectors are clearly going to be hardest hit by this. The ONS data shows that everyone who can likes going out in the UK. But that’s not going to happen with bills rising this much. There is going to be economic meltdown in these sectors.

Third, once these secondary effects kick in so does the financial crisis as debts, rents and mortgages, as well as utility bills, go unpaid. People without the money to pay their debts cannot settle them. The consequence is that a full-blown debt and banking crisis is on the cards.

How big a crisis? Something that makes 2008 look like a picnic, I suggest. That’s the magnitude of the crisis that we are looking at if people simply cannot pay their bills, as seems likely based on this quite fair data analysis of the problems most households are facing.

So, what can government do? I stress I ask that question in that way deliberately. That’s because I can’t see anyone else doing anything about this crisis, or having the power to do so. It is either down to the government to tackle this or we are in very deep trouble indeed.

First, the government has to acknowledge this problem, and its scale. Rishi Sunak has the chance to do that in his spring statement next week. I cannot see that happening but have to hope I am wrong.

My problem is that I recall all too well Sunak’s first response (and his second, and more) to Covid and they were all too little, too late, or riddled with holes that let fraudsters have a party at our expense. I have to hope that for once he might get this one right but doubt he will.

Second, the problem has to be acknowledged to be a universal one. It would be relatively easy to announce some measures for those on Universal Credit for example, and they’d be welcome. But, my data shows that the problem we are looking at extends way beyond those on UC.

Third, in that case tinkering of the sort announced earlier this year to tackle the increases in energy cost schedule for 1 April onwards are not going to be enough: something much more radical is required. Council tax rebates and enforced loan schemes won’t work this time.

Fourth, the problem is not only with domestic energy bills. I’ve shown that the increases in these are down to energy company profiteering that exploits us all in this thread.

The problem now extends to road fuel and food prices as well. Both are also likely to go up, and again because of profiteering in most cases because it is not cost increases that are driving up these prices, but shortages that are being exploited by speculators that are doing so.

Fifth, we have in that case an inflation driven crisis in our economy caused by speculators and not real cost increases from things that might compensate for the price increases, like wage rises.

Understanding this is important because it tells us what will not work to tackle this crisis. Most especially, increasing the official interest rate will do nothing to stop these speculators. All those increases will do is pour even more hardship on hard-pressed households.

In that case Rishi Sunak should be sending out a very clear signal to the Bank of England to not only stop the increases in interest rates they’re imposing on us right now, but to reverse them too. People need all the help they can get right now.

There is another message that Rishi Sunak also needs to be sending to the Bank of England, which is that he might need a lot more quantitative easing (QE) quite soon. The government’s response to Covid was entirely paid for with money created using QE.

No debt, no tax and no borrowing paid for the £400 billion cost of Covid. Money creation by the Bank of England did. And what we know is that money creation of this sort did not create inflation in the previous 11 years, and nor is it, or will it, now.

In that case, the crisis our economy now faces can be addressed using QE, if necessary. However, QE does create problems of growing inequality. To tackle them taxes on the best-off need to go up, and we will also need a windfall profits tax on energy companies.

What else can Sunak do? The answer is that he must intervene in markets to prevent the impact of the exploitation that we are seeing driving people into the financial problems that I am suggesting are likely to happen in this thread.

Tinkering will not do. Instead, he has to hit the problem head-on. He has to cut road fuel prices to prevent them pushing all other prices up. That means cutting VAT and other duties to keep these prices at 2021 levels. That’s the price we need to pay to beat inflation.

And then he has to be really radical. We need subsidised household energy pricing, imposed compulsorily on all energy suppliers. That means setting the tariff for the energy consumed by an average household at 2021 levels. The government must subsidise that cut in costs.

If this was done only larger houses should be required to pay the market price for whatever energy they consume above that average use. This would encourage energy-saving measures by them and suit the green agenda. That makes this fair, affordable and green.

These measures do, however, only address the immediate problem. Then we have to solve the long term one. That requires three things. Green energy; new jobs and better pay. This is where the Green New Deal comes in. This has always been designed to deliver all three, everywhere.

The jobs would be installing insulation to cut energy costs as more than 30% of UK houses are uninsulated at present. We also need more double glazing, and then heat pumps rather than gas boilers. On top of that, solar, wind, tidal and other new energy is required.

Then there is new green housing that is needed and the transformation of transport and office spaces. Just about every business process needs reengineering too. The number of jobs that becoming net-zero could create is enormous, as we cut our emissions.

All of this is affordable. QE and tax could pay a part. But so too could redirecting the financial wealth of the UK to this task. There is £8.4 billion of financial wealth in the UK, most in pensions funds and ISAs. The rules on these need to change to deliver green funding.

If ISAs had to be saved in government-backed green bonds paying competitive interest and one-quarter of all new pension contributions had to be used to fund the green transition more than £100 billion a year could be provided to create the transformation of our society.

Sunak could change ISA and pension rules to require that. Then we could be weaned off not just Russian gas and oil, but all the gas and oil that threatens life here on earth. This is possible. And we could have more, better-paid jobs using the savings.

In other words, we do not need to go into recession now. With imagination we could be setting ourselves up to tackle the immediate inflation issue and the long-term issue that created it. Will he do that? I don’t know. I can only hope so, for all our sakes.

What I do know is that if Sunak does little or nothing, we face the biggest economic meltdown of my lifetime with millions of households who have never faced poverty joining those who already know all about it. If that is not enough to make him act now, nothing is.

From Richard’s blog: Tax Research.org.uk