We are very grateful to Richard Murphy for allowing us to reproduce his excellent series of threads on important economic issues. Not everyone is on Twitter, so this enables us to get great content to those beyond our bubble.

We have just had another week when the media has obsessed about what they call the UK’s national debt. There has been wringing of hands. The handcart in which we will all go to hell has been oiled. And none of this is necessary. So this is a thread on what you really need to know

First, once upon a time there was such a thing as the national debt. That started in 1694. And it ended in 1971. During that period either directly or indirectly the value of the pound was linked to the value of gold. And since gold is in short supply, so could money be.

Then in 1971 President Nixon in the USA took the dollar off the gold standard, and after that there was no link at all between the value of the pound in the UK and anything physical at all. Notes, coins and, most importantly, bank balances all just became promises to pay.

A currency like ours that is just a promise to pay is called a fiat currency. That means that nothing gives it value, except someone’s promise. And the only promise we really trust is the government’s. Which means what we now have is really a national promise to pay.

If you don’t believe that it’s the government’s promise to pay that gives money its value, just recall when Northern Rock failed in 2007. There was the first run on a bank in the UK for 160 years. But the moment the government said it would pay everyone that crisis was over.

There’s a paradox here. We trust the government’s promise, which implies it has lots of money, and we get paranoid about the national debt, which suggests the government has no money. Both of those things can’t be right, unless there’s something pretty odd about the government.

And of course there is something really odd about the government when it comes to money. And that is that the government both creates our currency by making it the only legal tender in our country and also actually creates a lot of the money that we use in our economy.

How it makes notes and coin is easy to understand. They’re minted, or printed, and it’s illegal for anyone else to do that. But notes and coin are only a very small part of the money supply – a few percent at most. The rest of the money that we use is made up of bank balances.

The government also makes a significant part of our electronic money now. The commercial banks make the rest, but only with the permission of the government, so in fact the government is really responsible for all our money supply.

This electronic money is all made the same way. A person asks for a loan from a bank. The bank agrees to grant it. They put the loan balance in two accounts. The borrower can spend what’s been put in their current account. They agree to repay the balance on the loan account.

That is literally how all money is made. One lender, the bank. One borrower, the customer. And two promises to pay. The bank promises to make payment to whomsoever the customer instructs. The customer promises to repay the loan. And those promises make new money, out of thin air

If you have ever wondered what the magic money tree is, I have just explained it. It is quite literally the ability of a bank and their customer to make this new money out of thin air by simply making mutual promises to pay.

The problem with the magic money tree is that creating money is so simple that we find it really hard to understand. We can have as much money as there are good promises to pay to be made. It’s as basic as that. The magic money tree really exists, and thrives on promises.

But there’s a problem. Bankers, economists and politicians would really rather that you did not know that money really isn’t scarce. After all, if you knew money is created out of thin air, and costlessly, why would you be willing to pay for it?

What is more, if you knew that it was your promise to pay that was at least as important as the bank’s in this money creation process then wouldn’t you, once more, be rather annoyed at the song and dance they make about ever letting you get your hands on the stuff?

The biggest reason why money is so hard to understand is that it has not paid ‘the money people’ to tell you just how money works. They have made good money out of you believing that money is scarce so that you have to pay top dollar for it. So they keep you in the dark.

There are two more things to know about money before going back to the national debt. The first is that just as loans create money, so does repaying loans destroy money. Once the promise to pay is fulfilled then the money has gone. Literally, it disappears. The ledger is clean.

People find this hard because they confuse money with notes and coin. Except that’s not true. In a very real sense they’re not money. They’re just a reusable record of money, like recyclable IOUs. They can clear one debt, and then they can be used to record, or repay a new one.

The fact is that unless someone’s owed something then a note or coin is worthless. They only get value when used to clear the debt we owe someone. And the person who gets the note or coin only accepts them because they can use them to clear a debt to someone else.

So even notes and coin money are all about debt. They’re only of value if they clear a debt. And we know that. When a new note comes out we want to get rid of the old type because they no longer clear debt: they’re worthless. When the ability to pay debt’s gone, so has the value.

So debt repayment cancels money. And all commercial bank created money is of this sort, because every bank, rather annoyingly, demands repayment of the loans that it makes. Except one, that is. And that exception is the Bank of England.

So what is special about the Bank of England? Let’s ignore its ancient history from when it began in 1694, for now. Instead you need to be aware that it’s been wholly owned by the UK government since 1946. So, to be blunt, it’s just a part of the government.

Please remember this and ignore the game the government and The Bank of England have played since 1998. They have claimed the Bank of England is ‘independent’. I won’t use unparliamentary language to describe this myth. So let’s just stick to that word ‘myth’ to describe this.

To put it another way, the government and the Bank of England are about as independent of each other as Tesco plc, which is the Tesco parent company, and Tesco Stores Limited, which actually runs the supermarkets that use that name. In other words, they’re not independent at all.

And this matters, because what it means is that the government owns its own bank. And what is more, it’s that bank which prints all banknotes, and declares them legal tender. But even more important is something called the Exchequer and Audit Departments Act of 1866.

This Act might sound obscure, but under its terms the Bank of England has, by law, to make any payment the government instructs it to do. In other words, the government isn’t like us. We ask for bank loans but the government can tell its own bank to create one, whenever it wants.

And this is really important. Whenever the government wants to spend it can. Unlike all the rest of us it doesn’t have to check whether there is money in the bank first. It knows that legally its own Bank of England must pay when told to do so. It cannot refuse. The law says so.

As ever, politicians, economists and others like to claim that this is not the case. They pretend that the government is like us, and has to raise tax (which is its income) or borrow before it can spend. But that’s not the case because the government has its own bank.

It’s the fact that the government has its own bank that creates the national currency that proves that it is nothing like a household, and that all the stories that it is constrained by its ability to tax and borrow are simply untrue. The government is nothing like a household.

In fact, the government is the opposite of a household. A household has to get hold of money from income or borrowing before it can spend. But the gov’t doesn’t. Because it creates the money we use there would be no money for it to tax or borrow unless it made that money first.

So, to be able to tax the government has to spend the money that will be used to pay the tax into existence, or no one would have the means to pay their tax if it was only payable in government created money, as is the case.

That means the government literally can’t tax before it spends. It has to spend first. Which is why that Act of 1866 exists. The government knows spending always comes before tax, so it had to make it illegal for the Bank of England to ever refuse its demand that payment be made.

So why tax? At one time it was to get gold back. Kings didn’t want to give it away forever. But since gold is no longer the issue the explanation is different. Now the main reason to tax is to control inflation which would increase if the government kept spending without limit.

There is another reason to tax. That is that if people have to pay a large part of their incomes in tax using the currency the government creates then they have little choice but use that currency for all their dealing. That gives the government effective control of the economy.

Tax also does something else. By reducing what we can spend it restricts the size of the private sector economy to guarantee that the resources that we need for the collective good that the public sector delivers are available. Tax makes space for things like education.

And there is one other reason for tax. Because the government promises to accept its own money back in payment of tax – which overall is the biggest single bill most of us have – money has value.

It’s that promise to accept its own money back as tax payment that makes the government’s promise to pay within an economy rock solid. No one can deliver a better promise to pay than that in the UK. So we use government created money.

So, what has all this got to do with the national debt? Well, quite a lot, to be candid. I have not taken you on a wild goose chase to avoid the issue of the national debt. I’ve tried to explain government made money so that you can understand the national debt.

What I hope I have shown so far is that the government has to spend to create the money that we need to keep the economy going, which it does every day, day in and day out through its spending on the NHS, education, benefits, pensions, defence and so on.

And then it has to tax to bring that money that it’s created back under its control to manage inflation and the economy, and to give money its value. But, by definition it can’t tax all the money it creates back. If it did then there would be no money left in the economy.

So, as a matter of fact a government like that of the UK that has its own currency and central bank has to run a deficit. It’s the only way it can keep the money supply going. Which is why almost all governments do run deficits in the modern era.

And please don’t quote Germany to me as an exception to this because it, of course, has not got its own currency. It uses the euro, and the eurozone as a whole runs a deficit, meaning that the rule still holds.

So deficits are not something to worry about, unless that is you really do not want the UK to have the money supply that keeps the economy going, and I suspect you’d rather we did have government money instead of some dodgy alternative.

But what of the debt, which is basically the cumulative total of the deficits that the government runs? That debt has been growing since 1694, almost continuously, and pretty dramatically so over the last decade or so, when it has more than doubled. Is that an issue?

The answer is that it is not. This debt is just money that the government has created that it has decided not to tax back because it is still of use in the economy. That is all that the national debt is.

Think of the national debt this way: it’s just the future taxable income of the government that it has decided not to claim, as yet. But it could, whenever it wants.

That’s one of the weird things about this supposed national debt. When we’re in debt we can’t suddenly decide that we will cancel the debt by simply reclaiming the money that makes it up for our own use. But the government can do just that, whenever it wants.

This gives the clue as to another weird thing about this supposed national debt. It really isn’t debt at all. Yes, you read that right. The national debt isn’t debt at all.

That’s because, as is apparent from the description I have given, the so-called national debt is just made up of money that the government has spent into the economy of our country that it has, for its own good reasons, decided to not to tax back as yet.

So, the national debt is just government created money. That is all it is. But the truth is that the people of this country did not, back in 1694 when interest rates were much higher than they are now, like holding this government created money on which no interest was paid.

You have to remember something else about those who held this government created money in times of old. They were the rich. If you don’t believe me go and read Jane Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’ and note how much Bingley had in 4% government bonds.

And there was something about the rich, then and now. They get the ear of government. And so their protests about ending up with government money without interest being paid were heard. And so, money it might be, but from the outset the national debt had interest paid on it.

The so-called national debt still has interest paid on it. But then so do bank deposit accounts. And they look pretty much like money too. Only, they’re not as secure (at least without a government guarantee in place) and so the government can pay less.

But let’s be clear what this means. The national debt is money that represents the savings of those rich or fortunate enough to have such things on which interest is paid by the government because it’s been persuaded to make that payment.

Let me also be clear about something else. Those savings are not in a very real sense voluntary. If the government decides to run a deficit – and that is what it does do – then someone else has to save. This is not by chance it is an absolute accounting fact.

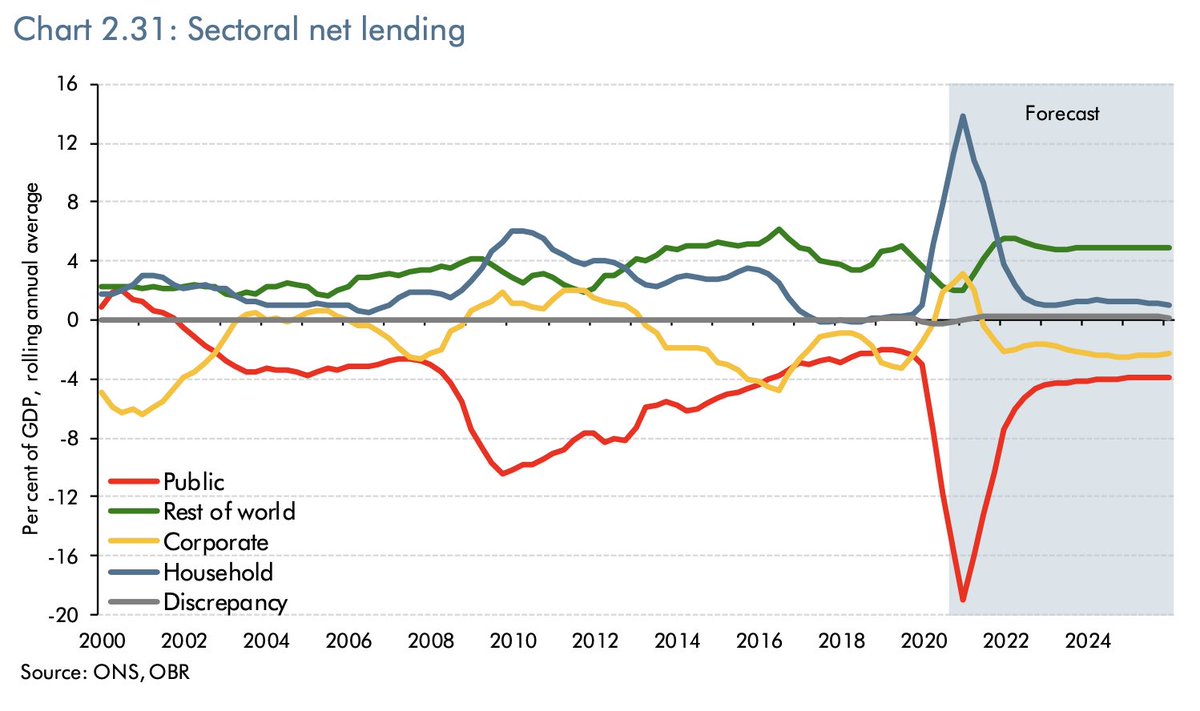

Where money is concerned for every deficit someone has to be in surplus. To be geeky for a moment, this is an issue determined by what are called the sectoral balances. There’s a government created chart on these here

The chart makes it clear that when the government runs a big deficit – as it did, for example, in 2008 – then someone simply has to save. They have no choice. And what they save is government created money. Which is exactly what is also happening now.

A growing deficit is always matched by savings. So who is saving? I am deliberately using approximate numbers, because they can quite literally change by the day. But let’s start by noting that the most common figure for government debt was £2,100 billion in December 2020.

Of this sum, according to the government, £1,880 billion was government bonds, £207 billion was national savings accounts and the rest a hotch-potch of all sorts of offsetting numbers, like local authority borrowing. I don’t think they do their sums right, but let’s start there.

Except, these official figures are wrong. Why? Because at the end of December the Bank of England had used what is called the quantitative easing process to buy back about £800 billion of the government’s debt, with that figure scheduled to rise still further in 2021.

I don’t want to explain QE in detail here, because I have already done that in another thread, that I posted as a blog here:

So let’s, taking QE into account, discuss what really makes up the national debt, starting with an acknowledgment that if the government owns around £800bn of its own bonds they cannot be part of the national debt because they are literally not owed to anyone.

Around £200 billion of the national debt is made up of National Savings & Investments accounts. That’s things like Premium Bonds, and the style of really safe savings accounts older people tend to appreciate.

Around £400 billion of the national debt is owned by foreign governments, which is good news. They do that because they want to hold sterling – our currency. And that’s because that helps them trade with the UK, which is massively to our advantage.

But what’s also the case is that that because of QE UK banks and building societies have around £800bn on deposit account with the Bank of England right now. This is important though: this is the government provided money stops them failing in the event of a financial crisis.

And then there’s very roughly £700 billion of other debt if the Office for National Statistics have got their numbers right (which I doubt). Whatever the right figure, this debt is owned by UK pension funds, life assurance companies and others who want really secure savings.

Why do pension funds and life assurance companies want government debt? Because it’s always guaranteed to pay out. So it provides stability to back their promise to pay out to their customers, whether pensioners, or life assurance customers, or whoever.

So now I have explained how we get a national debt and that it’s a choice to have one made by government. I’ve also explained that all it represents is the savings of people. And I’ve explained the government could claim it back whenever it wants. And I’ve covered QE.

So, the question is in that case, which bit of the national debt is so worrying? Do we not want people to save? Or, would we rather that they had riskier savings that our pensions at risk? Is that the reason why we want to repay the national debt?

Or do we want to stop foreign governments holding sterling to assist their trade, and ours?

Alternatively, do we want to take the government created money back out of the banking system when it’s saved it from collapse twice now (2009 and 2020) and which provides it with the stability that it needs to prevent a banking crash?

Or is it the national debt paranoia really some weird dislike of Premium Bonds that suggests that they are going to bring the UK economy down?

The point is, once you understand the national debt it’s really not threatening at all. And what you begin to wonder is why so many people obsess about it. To which question there are three possible answers.

The first is that the obsessive do not understand the national debt. The second is that they do understand it, but want to make sure you don’t. And the third is that they realise that if you did understand the national debt there would be no reason for austerity.

Of these the last is by far the most likely. There’s always been a conspiracy to not tell the truth about money, and how easily it’s made. There’s also a conspiracy to not tell the truth about the fact government spending has to come before taxation, and the law guarantees it.

And I strongly suggest that the hullabaloo about the national debt – which is a great thing that there is absolutely no need to repay and which is really cheap to run – is all a conspiracy too.

The truth is that the national debt is our money supply. It keeps the economy of our country going. It keeps our banks stable. And it also represents the safest form of savings, which people want to buy.

There is no debt crisis. Nor is the national debt a burden on our grandchildren. Instead, the lucky ones might inherit a part of it.

But some politicians do not want you to know that there is no real constraint on you having the government and the public services you want. What the government’s ability to make money, sensibly used, proves is we do not need austerity. And we never did.

Instead, the opportunity we want is available. And we do not need the private sector to deliver it. The government can and should take part in that process as well, which it can do using the money it can create as the capital it needs to do so.

But in order to pursue their own private gains and profits some would rather that this is not known, so they promote the idea that money is in short supply and that the national debt is a danger. Neither is true. We need to leave those myths behind. Our future depends on doing so

The end….for now.

Originally tweeted by Richard Murphy (@RichardJMurphy) on 02/03/2021.