This article, on the repeal of the Fixed Term Parliaments Act (FTPA), raises a question that needs more public discussion: who wields the historic powers of the Crown once the monarchy is no longer politically active? Should there be any limit on their use by a prime minister?

Some of the highest powers of the British state still technically belong to the Crown: from declaring war and making treaties to suspending Parliament. Those powers are now exercised “on the advice of the PM”. But they do not belong to the PM, and might, in theory, be withheld.

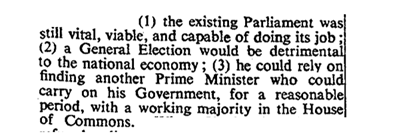

For example: the 1950 “Lascelles Principles” set out three conditions under which a monarch might refuse to dissolve Parliament (a “Royal Prerogative” pre-2011). Others might include “when the Opposition is in the middle of a leadership contest” or “when electoral fraud is suspected”

In effect, the monarchy became the “emergency brake” of the constitution. It could not exercise these powers itself, but it could stop a govt from doing so. It could deny a PM access to the “nuclear weapons” of the constitution: like the power to declare war or suspend Parlt.

This was never a very satisfactory brake. It relied on one person with no democratic authority, who might be inept, corrupt or Prince Andrew. And as Britain evolved from a “constitutional” to a “ceremonial” monarchy, it grew ever less likely that a monarch would actually use it

The reluctance of the monarchy to interfere in “politics” is obviously welcome. A democracy should not depend on a hereditary institution to protect it from the abuse of power. But it raises an important question: who, if anyone, should take over its constitutional functions?

Under the UK system, a PM can take office with no majority in Parliament and no direct electoral mandate, following an internal election among party members. It would be odd if there were no limit on their power to declare war, sign treaties or shut Parlt. So who now holds the brake?

In some cases, the Crown’s powers have moved to Parliament. The Fixed Term Parlt Act required MPs, not the monarch, to consent to an early dissolution. Both Blair and Cameron sought parliamentary approval for the use of armed force (though Theresa May tried to roll this back).

In other areas, the courts have intervened to limit the use of prerogative powers. Most famously, in 2019, the Supreme Court quashed the prorogation of Parliament as an abuse of power. It was now the Courts that were acting as the “emergency brake” of the constitution.

The new Dissolution Act reverses both tendencies. It shuts down any role for Parliament in preventing an early dissolution, & forbids the courts from intervening. That leaves only the monarch as a check, and the government makes clear that its role is to be purely ceremonial.

The govt’s “Dissolution Principles”, published alongside the Bill, remind the monarch that they should never be drawn into political controversy. There is no mention of the Lascelles Principles or of any other circumstances in which a dissolution might legitimately be denied.

For a democracy to transfer power from Parliament to the Crown is bizarre in itself. And the effect is to remove any check on the ability of a Prime Minister, who might have no majority and no electoral mandate, to access the highest powers of the state. Are we sure that’s wise?

The FTPA had many flaws, but the principle was sound: prerogative powers should be regulated by statute, not handed wholesale to anyone who can win an internal party election. The return of the Royal Prerogative raises serious constitutional questions. This bill gives the wrong answers.

Originally tweeted by Robert Saunders (@redhistorian) on 02/08/2021.